As ACE celebrates its centennial in 2018, this is one in a series of posts that looks at how ACE initiatives have left an impression on the higher education landscape and impacted peoples’ lives.

Achieving equitable access to college for communities of color has been a critical goal for higher education since the passage of the Civil Rights Act in 1964 and the Higher Education Act in 1965. So too has been recognizing and protecting institutional autonomy and freedom to construct a diverse campus that generates educational benefits for its students and allows it to fulfill its educational mission.

Diversity can mean different things to different campuses, from putting together a student body that has artists, dancers, tuba players, students from other countries, and athletes for its sports teams, to offering admission to students from a wide range of socio-economic backgrounds and racial and ethnic backgrounds. It is that range of individuals that leads to the educational benefits that accrue to students from being in a setting where they are surrounded by people of differing backgrounds and perspectives and who are interested in different things.

Time and again, ACE has echoed the U.S. Supreme Court’s affirmations of the benefits of campus diversity summarized most recently in its second ruling on Fisher v. University of Texas at Austin (Fisher II) in 2016: “the destruction of stereotypes, the promotion of cross-racial understanding, the preparation of a student body for an increasingly diverse workforce and society, and the cultivation of a set of leaders with legitimacy in the eyes of the citizenry.”

Similarly, ACE has emphasized the Supreme Court-sanctioned right of colleges and universities to pursue the version of diversity that best suits their own missions and goals, including through the limited consideration of race. This year, ACE and 36 higher education groups filed an amicus brief opposing the current challenge to diversity in admissions policies playing out in a federal courthouse in Boston—Students for Fair Admissions, Inc., v. Harvard.

The Council has worked to promote diversity in higher education since its early days. In 1946, ACE included recommendations for removing barriers to higher education for racial, religious, and handicap minorities in its Presidential Commission on Higher Education for President Harry S. Truman. In 1962, ACE formed the Committee on Equality of Educational Opportunity in the wake of issues that were raised during the integration of the University of Mississippi. Two years later, ACE established the Office of Urban Affairs, which evolved into the Office of Minorities in Higher Education. The office issued reports and publications on access and diversity on campuses, continuing a priority area for research first established in the 1940s.

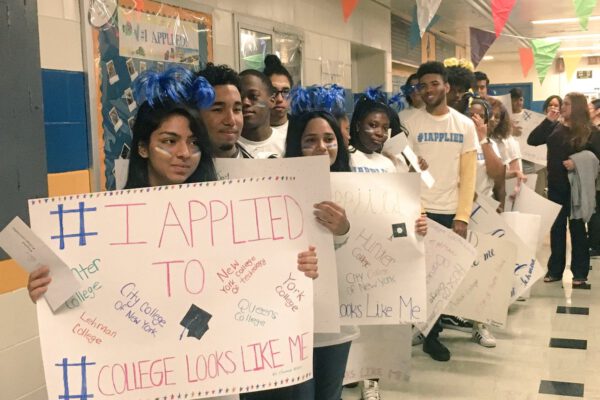

During the twenty-first century, ACE spearheaded a number of successful initiatives to broaden postsecondary access for previously underrepresented student populations. The Council worked with the Ad Council and the Lumina Foundation in 2007 to create KnowHow2Go, a program designed to help low-income, first-generation middle school students prepare for college. In 2011, ACE launched the American College Application Campaign, a state-based national initiative to assist low-income, first-generation high school seniors complete and submit at least one college application. That same year, ACE helped convene the National Commission on Higher Education Attainment to improve college student retention and degree completion.

ACE is a strong proponent of colleges and universities having the ability to define for themselves, within broad limits, the diversity that will produce the educational benefits they seek for all their students, including the consideration of race in admissions. Contemporary admissions policies in support of this goal have faced numerous legal challenges. In five different decisions over the past four decades, the U.S. Supreme Court has held in favor of the holistic consideration of race and ethnicity in college admissions as one of many factors, affirming the argument and research that shows student body diversity bestows myriad educational benefits. ACE submitted amicus briefs in most of these cases, including the 2003 University of Michigan cases Grutter v. Bollinger and Gratz v. Bollinger, as well as the Fisher v. University of Texas at Austin case, which was decided by the Supreme Court in 2013 and again when Fisher appealed and the Court again sided with the university in 2016 (known as Fisher II).

In response to the need for greater understanding of diversity in undergraduate admissions, ACE’s Center for Policy Research and Strategy (CPRS) published a groundbreaking study in 2015 called Race, Class, and College Access: Achieving Diversity in a Shifting Legal Landscape.

Coauthored by ACE, Pearson’s Center for College & Career Readiness, and the Civil Rights Project at the University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA), the report examined contemporary admissions practices at 338 four-year colleges and universities that collectively enrolled more than 2.7 million students and fielded more than 3 million applications for admission in 2013–14.

While the consideration of race in the admissions process varied, study participants affirmed that racial and ethnic diversity is a top priority for their institutions and that they used a variety of approaches to attract, admit, and enroll students of color. The most widely used diversity strategies included articulation agreements, targeted recruitment, and additional admissions consideration for community college transfers. The strategies perceived as most effective by admissions and enrollment management leaders included targeted yield initiatives, holistic application review, bridge or summer enrichment programs, and targeted financial aid.

The researchers also discovered that institutional reactions to the Supreme Court’s decisions are evolving. Although admissions offices had made modest changes after the first Fisher ruling in how they approach enrollment data, admissions factors, and diversity strategies, some institutions had placed increased importance on the recruitment of community college transfers and students from low-income backgrounds. This was especially true for institutions in states that had banned the consideration of race in admissions, which supersedes Supreme Court rulings.

“One of the challenges for American higher education in the wake of the [first] Fisher decision has been the lack of effective exchange of research, data, and plans,” said Gary Orfield, distinguished professor and co-director of the Civil Rights Project at UCLA. “Advancing equal educational opportunity requires sharing lessons learned in pursuit of promising diversity strategies. The story of affirmative action law and policy is still unfolding and researchers must respond to the needs of institutions.”

Moving forward, ACE’s work on expanding diversity in higher education continues. In 2019, ACE’s Center for Policy and Research Analysis will release the results of a study examining gaps and progress in educational attainment for historically underrepresented student populations. The project, Race and Ethnicity in Higher Education: A Status Report, also will assess the diversity issues within the pipeline to the professoriate and postsecondary leadership. Stay tuned.

If you have any questions or comments about this blog post, please contact us.