Early in my career as an education data analyst, I was chatting with the new counselor at a rural Georgia high school. She described a particularly challenging student named “Joey,” a troubled but bright young sophomore. When she sought advice from a veteran teacher, the response was disheartening: “Honey, don’t you worry about that child. We’ve had problems with that family for generations.”

The implication was that Joey—and many other students and families who live among us—would inevitably live out a life script that the local community had preordained for them. This notion has troubled me ever since, and I have found myself wondering what we can do as campus and community leaders to open up alternative paths for those whose lives seem more filled with obstacles and pitfalls than opportunities and options. What can we do to bring out the potential existing within these students?

I was recently reminded of this exchange as the Alabama Commission on Higher Education began to evaluate our work to improve college access to students through an initiative to increase Free Application for Federal Student Aid (FAFSA) completion. Recognizing the significant financial barrier preventing many Alabama students from pursuing higher education, the State Board of Education implemented a groundbreaking policy in April 2021. This policy mandates that every graduating senior must complete the FAFSA, a crucial step in accessing potential grants and scholarships, with the option of a waiver subject to approval.

The decision was driven by compelling statistics: Annually, Alabama high school graduates collectively leave an astonishing $47 million in federal aid on the table due to incomplete FAFSA forms. Research by the National College Attainment Network found that 92 percent of high school graduates who complete the FAFSA are significantly more likely to enroll in college the following fall. Given that the vast majority of Alabama high school students qualify for some form of federal financial assistance, this policy change was viewed as the key to improving college access.

Before the FAFSA requirement was enacted, our efforts to improve FAFSA completion emphasized professional development for high school guidance counselors and other college advising staff. We saw some progress, but many districts and counties saw little improvement. Discouragingly, the lowest levels of improvement in FAFSA completion were found in areas with the greatest proportion of low-income students—students who stood to benefit the most from access to need-based aid and available grants and scholarships. I attributed these modest gains—at least in part—to the “Joey effect” of local efforts being hampered by preconceived expectations of students. With limited resources available, help was given to those students who were deemed to be “college material,” while many other students never realized there were opportunities beyond others’ limited expectations for them.

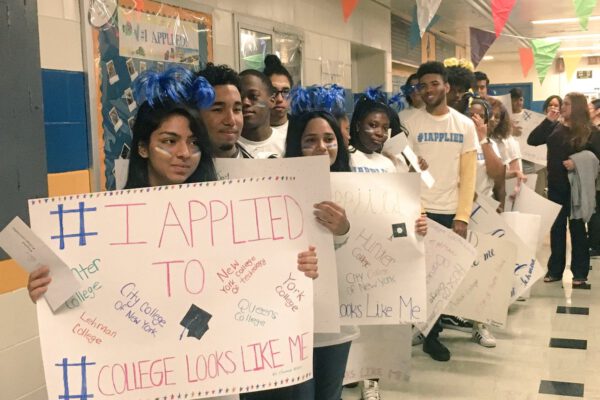

The FAFSA graduation requirement proved to be a game-changer for our efforts to improve access to higher education, primarily through its emphasis on direct and consistent communication with students to let them know that college is a possibility. In support of the requirement, the commission developed a dashboard of high school and school district performance to motivate students and high school staff to complete the FAFSA. To further support this endeavor, we established direct communications with high school seniors. Using email communications to all public high school seniors, we emphasized the importance of completing the FAFSA for going to college. We developed a series of automated emails to help students resolve specific issues with their FAFSA applications. The initiative yielded immediate results the first year with Alabama high school seniors increasing the state’s FAFSA completion rate by 30 percent. The financial investment of $500,000 for these direct communications increased the awarding of FAFSA funds by $13,100,000.

Notably, three of the state’s poorest counties saw dramatic improvements. Barbour County went from 25 percent of its senior class completing a FAFSA to 86 percent, Sumter County 37 to 76 percent and Choctaw County 40 to 92 percent. Perhaps equally impressive, the improvement was sustained in the second year of the initiative with the FAFSA completion rate rising to 91 percent for Barbour, 88 percent for Sumter, and 93 percent for Choctaw.

As this new academic year begins, let’s make sure our students know that we want them to be successful in college, in work, and in life. The dramatic improvements in FAFSA completion rates in some of our state’s most challenged counties demonstrate the power of direct outreach and unwavering belief in our students’ potential.

However, the work is far from over. The recent challenges with the U.S. Department of Education’s launch of the new FAFSA underscore the persistent barriers faced by students from disadvantaged backgrounds. We must continue to innovate and adapt our strategies to ensure that every student, regardless of zip code or family background, has the opportunity to pursue higher education. I propose that states throughout the country actively pursue new policies and processes to improve access to college, including exploring alternative pathways to admission. By refusing to accept the “Joey effect,” we can create a future where all students can realize their full potential.

Photo by Andrea Mabry | UAB

If you have any questions or comments about this blog post, please contact us.