The Shifting Demographics of College Enrollment from 2009 to 2019

Title: Progress Interrupted: Evaluating a Decade of Demographic Change at Selective and Open-Access Institutions Prior to the End of Race-Conscious Affirmative Action

Authors: Jeff Strohl, Emma Nyhof, and Catherine Morris

Source: Georgetown University Center on Education and the Workforce

An uncertain job market and a precarious economy drove students of all types to enroll in postsecondary education during the Great Recession, but this trend did not continue past the height of the economic downturn. To pinpoint the origins of the enrollment decline from 2009 to 2019, researchers at the Center on Education and the Workforce at Georgetown University examined trends by school selectivity, student socioeconomic status (SES), gender, and race and ethnicity in a new report.

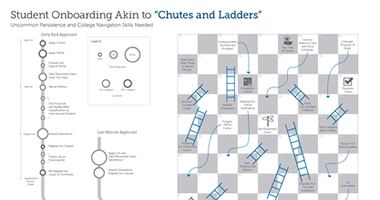

The pandemic further shocked student demographics. Despite some recovery, enrollment totals have not returned to 2019 levels, and the upcoming demographic dropoff indicates that this decline will not improve in the short term. Moreover, enrollment is one of the first steps in getting a postsecondary degree and students are increasingly juggling financial and familial responsibilities, making affording and graduating from college even more challenging.

Pell Grant recipiency is often used as a proxy for SES. At the 498 US institutions considered selective, less than a quarter (24 percent) of students received a Pell Grant in 2019, compared to 56 percent at open-access institutions. At the 92 most selective institutions in America, only 17 percent of students received Pell Grants.

According to the analysis, gaps exist between the racial and ethnic makeup of the national high school graduating class and that of the first-year class at selective institutions later that fall. White and Asian American or Pacific Islander students enroll at selective institutions at much higher rates than other racial and ethnic groups.

According to the report, to reach parity with the high school graduating class, the share of Black, Hispanic, and Indigenous students at selective institutions would need to increase by 19 percentage points and the share of low-SES students would need to increase by 30 percentage points. High-SES students from all racial and ethnic groups are better represented than their low-SES counterparts at selective schools, but high-SES Black students are still underrepresented in comparison to their national high school cohort.

In total, enrollment of Pell Grant recipients peaked in 2009 and has been trending downward ever since. That peak figure, though, can be partially attributed to modifications to eligibility parameters and an increase to the maximum grant amount enacted between 2007 and 2009.

Overall and across all racial and ethnic groups, graduation rates increased with institution selectivity. At the 498 most selective American institutions, 78 percent of students graduated, compared to fewer than two in five students at open-access institutions (37 percent). This pattern holds true when further disaggregating selective schools by competitiveness.

Gaps persist between female and male graduation rates too at both open-access and selective institutions. However, the size of these gaps varies by racial and ethnic group. At both institution types, the gender gap for graduation rates was smallest among White students. Whereas 42 percent of White women and 39 percent of White men graduate at open-access institutions, a 3 point gap, 31 percent of Black/African American women and 25 percent of Black/African American men graduate at the same institutions, a 6 point gap. These disparities are even more pronounced at selective institutions: 81 percent of White women and 76 percent of White men graduate, a 5 point gap, compared with 70 percent of Black women and 60 percent of Black/African American men, a 10 point gap.

The disparities in enrollment rates between selective and open-access institutions have considerable implications for student outcomes, especially graduation rates and long-term financial stability. High sticker prices deter low-income students from applying to and attending more selective institutions, where student services are abundant and graduation rates are higher. To improve access to selective institutions for low-income, historically underrepresented students, changes must be made to the K-12 system to enhance direct pathways to postsecondary education.

Click here to read the full report.

—Erica Swirsky

If you have any questions or comments about this blog post, please contact us.