As ACE celebrates its centennial in 2018, this is one in a series of posts that look at how ACE initiatives have left an impression on the higher education landscape and impacted peoples’ lives.

Throughout its history, ACE has worked to support the inclusion of women in all aspects of higher education. From advocating women’s right to work in the 1920s to creating a pipeline to higher education leadership positions in recent years, ACE has spearheaded a number of initiatives focused on women and their success.

Women’s Right to Work

In 1920, the year women gained the right to vote through the 19th Amendment to the Constitution, ACE established the Committee on the Training of Women for Professional Service. The committee advocated for women’s right to work and broadened options for their education and professional advancement.

Several decades later, with the onset of the Cold War and the Korean conflict in the early 1950s, ACE convened a conference to explore “urgent questions about just how…women could serve the defense of the nation,” including military service, industrial work, and efforts in the home. More than 900 educators, government representatives, businesspeople, and citizens attended the Conference on Women in the Defense Decade. They concluded that the modern woman needed higher education to become “politically literate and…conscious of her responsibilities as a citizen in a democracy.”

To that end, ACE established the Commission on the Education of Women (CEW) to focus on radically expanding the options for women in higher education, giving them greater access to courses and degrees in fields previously dominated by men. Operating from 1953 to 1962, CEW issued two publications: How Fare American Women? in 1955 and The Span of a Woman’s Life and Learning in 1960. Both challenged the traditional notion that a liberal arts or home economics track was sufficient for women pursuing a postsecondary degree.

As the commission’s studies circulated, campuses across the country reexamined their continuing education options for women of all ages and stages of life. By 1971, there were more than 500 programs to assist women in entering or reentering college in order to garner broader career choices and workplace options.

The Civil Rights Era

Meanwhile, ACE advocated for Title VII of the Civil Rights Act in 1964, which prohibited employment discrimination based on gender. The momentum for women’s rights picked up in the 1970s with the passage of Title IX of the Education Amendments of 1972, which prohibited sex discrimination in all aspects of educational programs that receive federal support.

In response, ACE created the Office of Women in Higher Education (OWHE) in 1973. OWHE not only provided guidance for on-campus compliance with Title IX legislation, but also set its sights on increasing the number of women in leadership positions, with special emphasis on presidencies, vice presidencies, and deanships.

In 1977, after concluding that qualified women were available but overlooked, OWHE launched the National Identification Program for the Advancement of Women in Higher Education, known as ACE/NIP. Its objective was to identify talented women and enhance their visibility as leaders by holding national, state, and regional forums that addressed key leadership issues such as finance and ethics in education, the role of trustees, and importance of diversity to the educational mission. ACE/NIP was a success, as evidenced by the 225 percent increase (from 148 to 480) in women presidents at U.S. colleges and universities from 1975 to 1999.

The Fight Is Not Over

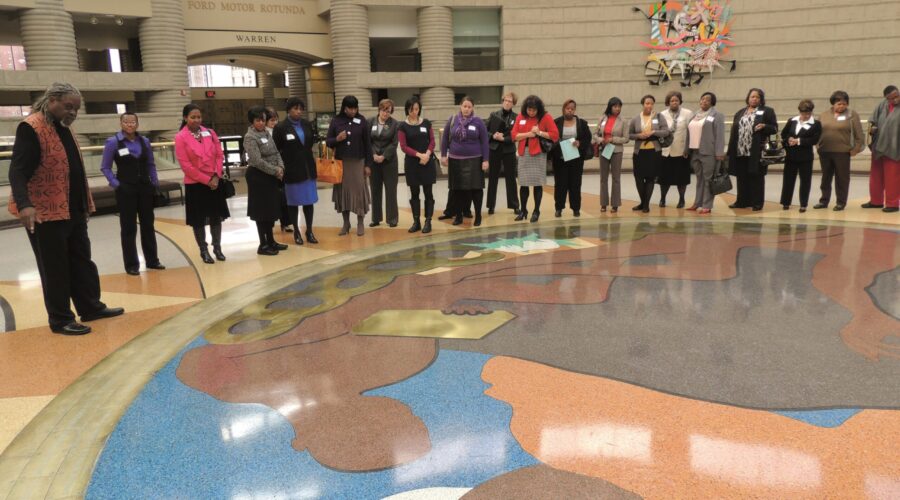

Today, the ACE/NIP program continues as the ACE Women’s Network and connects women pursuing higher education leadership opportunities through independent networks that engage state chairs, presidential sponsors, and institutional representatives. These independent networks create programs and resources that identify, develop, encourage, advance, link, and support (IDEALS) women in higher education careers. The ACE Women’s Network Executive Council supports state networks by serving as a liaison and mentor to state chairs and as a leader for network planning boards.

In 2012, the ACE Women’s Network Executive Council and ACE’s Inclusive Excellence Group convened more than 30 representatives from a variety of institutions and associations to discuss the gap between the percentage of female graduates (a 59 percent majority of all degrees) and the percentage of female higher education executives (just 26 percent of all college presidencies at the time). The result was the 2016 launch of the Moving the Needle commitment. This initiative outlines a long-term plan to advance women in higher education leadership and achieve gender parity, with 50 percent women at senior-level, decision-making, and policy-making levels by 2030.

Margaret L. Drugovich, chair of the ACE Women’s Network Executive Council beginning in 2016, identified the importance of awareness, research, and advocacy on behalf of women leaders in higher education: “I think that women and men need to understand that women do not need to be more to be equal. We don’t need to be more perfect; we don’t need to be more transparent or more understanding or more patient or more compassionate or more intelligent just to be equal. I think it’s time for people to recognize that simply being a woman is enough or, often, more than enough to get the challenge done.”

If you have any questions or comments about this blog post, please contact us.